When Charles Dickens published his career-changing work in December 1843, Christmas was not the major holiday we think of today. In fact at that time it ranked somewhere beneath Easter in importance on the Christian calendar. But a few things happened during the 19th century that would propel the holiday to near preeminence.

Dutch settlers of New York considered St. Nicholas their patron saint, and celebrated his day, December 6th, accordingly. On St. Nicholas Eve, they hung stockings with the hope St. Nicholas would visit and leave them presents. In 1809, Washington Irving (1783-1859) published his satirical History of New York under the nom de plume of Diedrich Knickerbocker. In it he fancied that St. Nicholas had a wagon he could ride over trees and rooftops. By 1821 the Dutch word for St. Nicholas, “Sinterklaas,” had been Anglicized into Santeclaus, thanks to an anonymously published poem by William Gilley of New York. The stage was set.

In 1823, and essentially by accident, a poem by Clement Clarke Moore (1799-1863) was published that would become one of the best-loved English language poems, “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” or as most of us know it, “The Night Before Christmas.”

And it was Moore that transplanted Santa’s visit and famous accompanying nocturnal events to Christmas Eve, inventing along the way each of Santa’s eight reindeer. By the time Dickens published his famous story, the poem was published regularly by newspapers across the country every Christmas Eve.

But well before Thomas Nast drew a lasting image of Santa Claus for the January 3, 1863 issue of Harper’s Weekly, Dickens smartly encapsulated the Christmas spirit in a novella that was equal parts parable, social criticism, and ghost story.

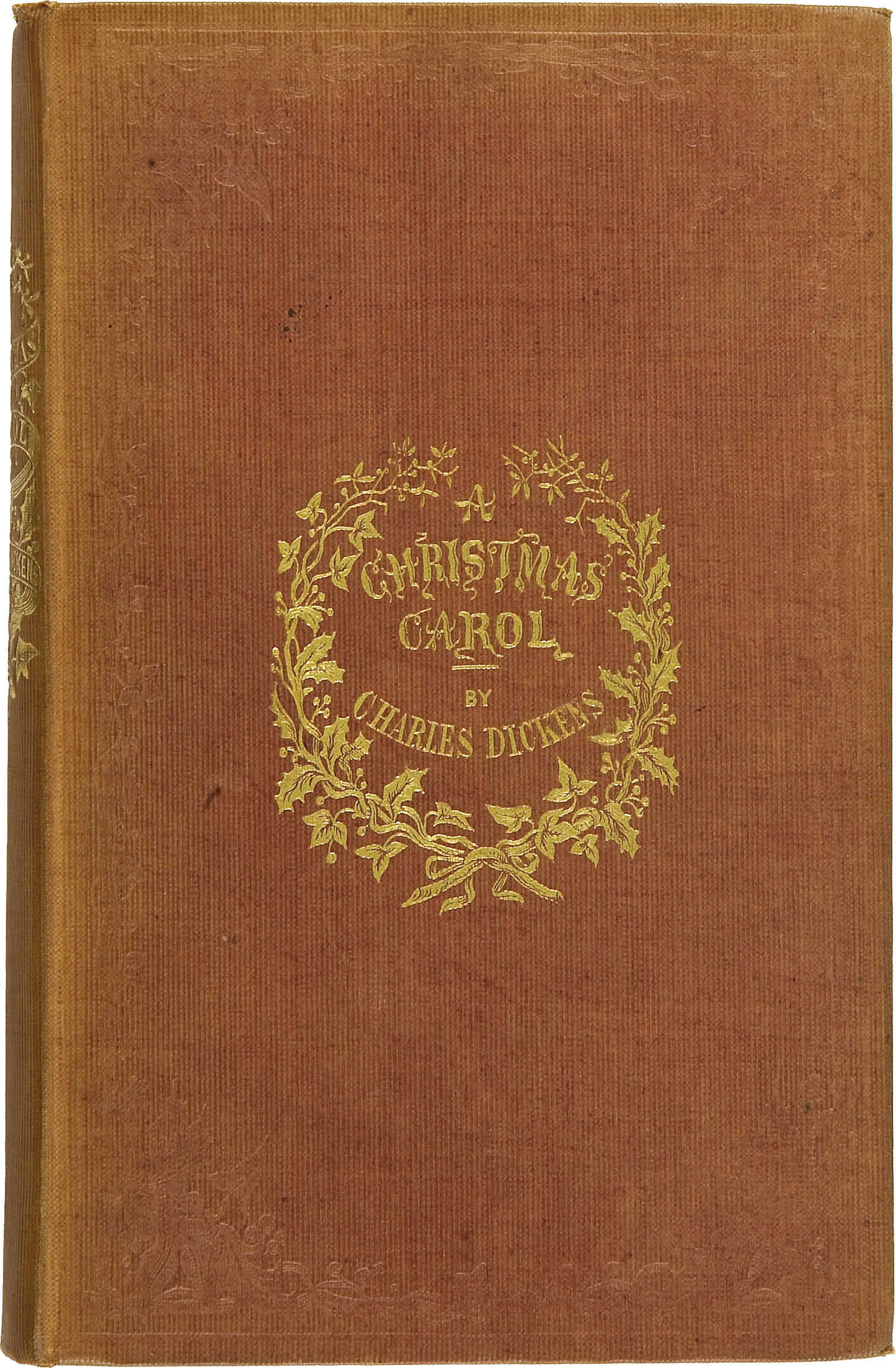

Published on December 19, 1843, the first edition of 6000 copies sold out that day. A further six editions comprising 7000 more copies would be executed by the end of January 1844.

Dickens had begun composition in October of 1843, under severe financial strain. A disagreement with his publisher led to him financing the edition himself, and he ordered expensive binding, gilt edging, and four hand-tinted illustrations by John Leech, all while insisting the price be kept at 5 shillings, so as to allow just about anyone to afford it.

Variants among the first and second editions are most numerous, with the earliest state of the first edition having green endpapers and uncorrected errors in the text and table of contents. Scholars have long debated various aspects of the editions and states, among them Richard Gimbel, Philo Calhoun, Howell J. Heaney, and William B. Todd. The debate goes as far as using measurements of the title and borders on the cloth front board to define an edition and state.

Scholarly consensus regarding the anatomy and qualities of the earliest editions may never come, but the timelessness of the story remains beyond doubt!

Did you find this post interesting? Click the dates and months on the Blog Archive side bar to the right for more! Thanks for reading!